My First Memory of Color

Short documentary by Anatoli Ulyanov

As an immigrant from a raceless country, I’m troubled by the American obsession with the color of one’s skin.

In 2018 I’ve asked my friends to recall the very first time they became aware of having a race.

ARTIST STATEMENT

Being born in the Soviet Union, I was never introduced to the concept of “Race”. Not until I moved to the United States and realized that everything in this country is about Color, and defined by Color. To me, it’s something that is hard to comprehend. As an immigrant who’s going through the process of re-socialization, I feel that Race is being forced on me – as if in order to become an American citizen I must include the color of my skin into my identity. I resist the racial cautiousness as a fertile soil for racism. But in the US a notion of Race seems to be bigger than a person. I use my art as a tool to investigate this problem and to provoke a discussion.

Los Angeles, 2018

VIDEO: Anatoli Ulyanov

DESIGN: by Natasha Masharova

MUSIC: The Bowls

PRODUCTION: VVHY

ОТ АВТОРА

Меня беспокоит американская одержимость цветом кожи. Я родился в советской Украине. Идея “расы” не была частью моего социалистического образования. Никто не учил меня ни тому, что я “белый”, ни тому, что “чёрные” чем-то “хуже” меня. Оказавшись в США, я попал в общество, где цвет кожи решает всё. Проходя через неизбежный для всякого иммигранта процесс ре-социализации, я чувствую как американская культура буквально принуждает меня к расе – складывается впечатление, что для того, чтобы стать американским гражданином я должен включить цвет кожи в свою идентичность. Я усматриваю в этом требовании расизм, и пытаюсь понять бытовую механику расового сознания. Поэтому и попросил своих американских друзей вспомнить первый раз, когда они осознали, что у них есть раса. Результатом этого опроса стало данное видео.

Remembering the Dead, Differently

by Fred Ritchin

by Fred Ritchin

In the United States, publications that have memorialized mass casualties have mostly concentrated on soldiers. Now, with the pandemic, it is civilians as well.

LIFE Magazine July 5, 1943

The cover of the July 5, 1943 issue of Life magazine, entitled “America’s Combat Dead,” displayed a photograph of six men from a U.S. fighter squadron carrying a flag-draped coffin of a member of their unit in Tunisia, where the burial would take place. Inside, there was a list of the names, but no identifying photographs, of the 12,987 American soldiers who had already died during the first 18 months of World War II. “That is the list. These are the boys who have gone over the Big Hill,” the magazine’s editorial began.

Why did they die? The editorial assigns the magazine’s readers the task of finding meaning in their deaths, if meaning can be found: “So it matters a great deal what we say the purpose is, it makes all the difference in the world: indeed, it is for us to decide whether he died for the fulfillment of a purpose, like the boys of the American Revolution, or whether he died for the fulfillment of practically nothing, like the boys of World War I. The dead boys will become what we make them.” On the table of contents, just over the assertion of copyright, there is a statement in all capital letters that “All photos and texts concerning the armed forces have been reviewed and passed by a competent military or naval authority.”

During World War II, text was used to commemorate combat casualties before photographs could be published that depicted these soldiers who had been killed.

Two months later, in the September 20 issue, Life would publish for the first time a photograph of the bodies of dead American soldiers. The three men lay half-buried in the sand on Buna beach, New Guinea, their faces not visible. George Strock’s photograph had been made eight months earlier, in January of that year, when such photographs were still being censored by the US government, concerned as to how Americans at home would react. The decision to allow the publication of the Buna beach photo is said to have been made in large part out of a desire to rouse a US public that had been growing complacent about the far-away war.

Life explained the publication of the Buna beach photograph to its readers: “The reason is that words are never enough. The eye sees. The mind knows. The heart feels. But the words do not exist to make us see, or know, or feel what it is like, what actually happens. The words are never right.” And, as Liam Kennedy writes in his essay, “Picturing Conflict,” the publication of this photograph is credited with having driven up the sale of war bonds, while government surveys made after its publication showed Americans increasingly supportive of the appearance of such graphic imagery.

During World War II, text was used to commemorate combat casualties before photographs could be published that depicted these soldiers who had been killed.

LIFE Magazine June 27, 1969

During the Vietnam War it was a different situation. Many extraordinary, sardonic, viscerally upsetting images of the battlefield appeared throughout the world, published in both black-and-white and color, that were made by photographers who were not bound by any allegiance to governments. It was, however, when simpler, toned-down identity-style photographs were published on June 27, 1969, in Life magazine as “The Faces of the American Dead, One Week’s Toll,” the cover featuring a portrait of U.S. Army specialist William C. Gearing, Jr., that the magazine was judged by many to have changed its editorial stance and to have become anti-war. The magazine’s managing editor, Ralph Graves, later remarked that “in his remaining tenure as editor he had never run anything as important or powerful.”

Here, it was no longer the repetitive recitation of statistics concerning each week’s dead that was sufficient, but the requirement that each person killed must be looked at and recognized as a unique individual.

Interestingly, it was not the many photographs of the gore and horror of the battlefield, but the photographs collected from family members of the great majority of the 242 soldiers killed that week, each captioned with the individual soldier’s name, age, rank and hometown, that unsettled the country. The magazine’s staff explained their decision: “Yet in a time when the numbers of Americans killed in this war—36,000—though far less than the Vietnamese losses, have exceeded the dead in the Korean War, when the nation continues week after week to be numbed by a three-digit statistic which is translated to direct anguish in hundreds of homes all over the country, we must pause to look into the faces. More than we must know how many, we must know who. The faces of one week’s dead, unknown but to families and friends, are suddenly recognized by all in this gallery of young American eyes.”

Here, it was no longer the repetitive recitation of statistics concerning each week’s dead that was sufficient, but the requirement that each person killed must be looked at and recognized as a unique individual.

In an update of this idea, more recently the New York Times published an ongoing online visual database “Faces of the Dead” that showed identity-style photographs of American war casualties (it is now archived). Here one was able to click on one of thousands of pixel-like squares to call up an image of a U.S. soldier killed in Iraq or Afghanistan; the thousands of dead were all contained within the same rectangle, all made to seem part of a single body. One was also able to search for the war dead by last name, hometown, or home state, allowing the reader to engage more independently with their deaths.

And, attracting millions of visitors each year, the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. lists on a black granite wall the names of more than 58,000 American soldiers who were casualties of that conflict, but does not include their photographs. In a manner similar to Life’s “Faces of the American Dead,” publications such as Vanity Fair have commemorated the lives of many of those from the world of culture who died from AIDS, presenting a gallery of photographs captioned with each individual’s name, occupation and age.

New York Times, May 24 2020

On Sunday, May 24, the New York Times created a front-page memorial for those Americans who have died from COVID-19 as the number approached 100,000—more than the combat casualties suffered by the US in every conflict since the Korean War. Filling the front page of the print newspaper and continuing onto inside pages with the names of 1,000 of the dead, their age and hometown, and a short phrase describing something important about each individual’s life, the Times explained that it wanted “to represent the number in a way that conveyed both the vastness and the variety of lives lost” while realizing “there’s a little bit of a fatigue with the data” that is reported daily. (There is another version published online.) The headline that went across the top of the front page stated, “U.S. DEATHS NEAR 100,000, AN INCALCULABLE LOSS.”

The Times’ staff decided not to publish any photographs. Instead, the front page became, with its myriad of names, an image itself. Many have questioned that decision, some referencing Life’s 1969 issue commemorating the American dead during one week of the Vietnam War, asking why readers cannot see the faces of those who have been lost. There are many conceivable answers, including the difficulties involved in both securing and printing 1,000 photographs.

It also may be that for many the photograph, once viewed as a way to establish and affirm one’s own identity or someone else’s, no longer has that role.

But it seems that now, when nearly everything is contested, when facts seem to matter less and the motivations for every action can be grotesquely distorted by others, it may be more respectful to the dead to keep their images out of the general fray. It also may be that for many the photograph, once viewed as a way to establish and affirm one’s own identity or someone else’s, no longer has that role. Instead the photograph is increasingly seen as an image to be manipulated for a variety of reasons and, as a result, can no longer be trusted.

This then makes it increasingly difficult, given the deep and angry fractures in society, to use photographs to assert a large-scale communal loss. The prisms through which photographs are looked at can no longer be assumed to be largely those of openness and solidarity. This too is an enormous loss.

So that we, unable to view their faces, are left to imagine, grieving and forlorn, those whom we have lost.

And to recognize that in the Age of Image there may be less that can be seen.

– Fred Ritchin, May 28, 2020

COMPLETE CAPTIONS

LIFE Magazine July 5, 1943

Through a wheat field in Tunisia six men of a U.S. fighter squadron are carrying a flag-draped coffin containing the body of a member of their outfit. The brief funeral is over; soon the burial, far from home, will be finished.

(Hart Preston/Life Pictures)

LIFE Magazine July 5, 1943

In a field of Tunisian, wheat, chaplain Rice conducts funeral service for a U.S. Pilot. Friends bow their heads in prayer.

(Hart Preston/Life Pictures)

LIFE Magazine June 27, 1969

“The Faces of the American Dead in Vietnam. One week’s toll. “

Cover featuring a portrait of U.S. Army specialist William C. Gearing, Jr., one of 242 American servicemen killed in a single week of fighting during the Vietnam War.

(Life Pictures)

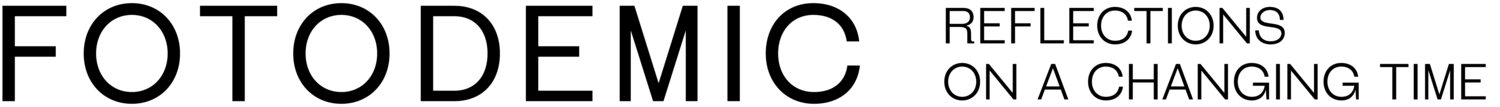

Fumiko

by Sayuri Ichida

by Sayuri Ichida

Fumiko is my mother.

Today, she is the person that I want to photograph the most.

Because that is not possible, I made this work to serve as a composite portrait of her as seen through the memories she left behind.

I was 20 and my mom was 47 when she passed away. She was a smoker and she died from lung cancer. When I learned that she was ill, I looked back and realized that she was constantly coughing. Even though she had been fighting with cancer for several years, I was not prepared for her death, I refused to acknowledge reality.

I blamed myself after her death because I didn’t go back home and spend time with my family on New Year’s day only three months before she passed. I chose to stay in Tokyo with my friends, because that somehow made it easier for me to believe that my mom would be OK.When she started slipping in and out of consciousness towards the end of her illness, one day she suddenly said in her bed, as if she had just remembered: “can we eat Japanese pancakes for tonight’s dinner?”

It looked like she herself also didn’t seem to understand that her own death was approaching.

It’s been more than ten years already. And in all these years whenever I dreamt about her, she looked sad and empty. Did the impact of witnessing my mom’s death wash away all my other memories of her? Was she always so sad and empty?

When she was healthy, she was always very self critical and uncertain about herself, but when she was fighting against her illness, she seemed confident and determined to win. When she lost all of her hair from radiation therapy and wore a wig for the first time, she made fun of herself and laughed very hard, even though my father, sister and I were all very concerned about how it might affect her. When she drove, she always played Chaka-kan and Whitney Houston. Every time she played these songs, my sister and I protested, but deep inside I was proud of her that she was listening to western music in a town so deep in the countryside as ours.

Early in 2017, my dad told me that our house was going to be demolished. The house was damaged by the 2007 Chuetsu-oki earthquake and it was never properly repaired since. I felt an emptiness inside me. My mom had been gone for ten years by this time, and now the house where I grew up was going to be demolished as well. In 2018 I went to where our house used to be and there was nothing but an empty lot that looked as if it had been there for years. There was only grass... And weeds moving with the wind.

A couple of years ago, I found an old metal cookie box in my parents’ old house, where they lived before they moved to Nigata. The box was full of images of my mom’s childhood and early adulthood, and many images of the early years of my parents’ relationship both before and after they got married.

Fumiko is my mother. Today, she is the person that I want to photograph the most as a photographer. Because that is not possible, I made this work to serve as a composite portrait of her as seen through the memories she left behind.

Sayuri Ichida was born in Fukuoka, Japan in 1985.

complete artist statement

I was 20 and my mom was 47 when she passed away. She was a smoker and she died from lung cancer. When I learned that she was ill, I looked back and realized that she was constantly coughing. Even though she had been fighting with cancer for several years, I was not prepared for her death, I refused to acknowledge reality.

I blamed myself after her death because I didn’t go back home and spend time with my family on New Year’s day only three months before she passed. I chose to stay in Tokyo with my friends, because that somehow made it easier for me to believe that my mom would be OK.

When she started slipping in and out of consciousness towards the end of her illness, one day she suddenly said in her bed, as if she had just remembered: “can we eat Japanese pancakes for tonight’s dinner?”

It looked like she herself also didn’t seem to understand that her own death was approaching.

It’s been more than ten years already. And in all these years whenever I dreamt about her, she looked sad and empty. Did the impact of witnessing my mom’s death wash away all my other memories of her? Was she always so sad and empty?

When she was healthy, she was always very self critical and uncertain about herself, but when she was fighting against her illness, she seemed confident and determined to win. When she lost all of her hair from radiation therapy and wore a wig for the first time, she made fun of herself and laughed very hard, even though my father, sister and I were all very concerned about how it might affect her. When she drove, she always played Chaka-kan and Whitney Houston. Every time she played these songs, my sister and I protested, but deep inside I was proud of her that she was listening to western music in a town so deep in the countryside as ours.

Early in 2017, my dad told me that our house was going to be demolished. The house was damaged by the 2007 Chuetsu-oki earthquake and it was never properly repaired since. I felt an emptiness inside me. My mom had been gone for ten years by this time, and now the house where I grew up was going to be demolished as well. In 2018 I went to where our house used to be and there was nothing but an empty lot that looked as if it had been there for years. There was only grass... And weeds moving with the wind.

A couple of years ago, I found an old metal cookie box in my parents’ old house, where they lived before they moved to Nigata. The box was full of images of my mom’s childhood and early adulthood, and many images of the early years of my parents’ relationship both before and after they got married. Fumiko is my mother. Today, she is the person that I want to photograph the most as a photographer. Because that is not possible, I made this work to serve as a composite portrait of her as seen through the memories she left behind.

母が亡くなったのは私が二十歳になってすぐの三月の終わり頃であった。 47歳だった。 その年の正月、新潟の実家に帰らず東京で友人と過ごした自分を恨んだ。母はすでに闘病生活を数年続けていたのに も関わらず、私は母が亡くなるなんて少しも想像できていなかったのだ。病室ですでに意識が遠のいていた母がふと 思い出したように言った。「今日の夕飯はお好み焼きでいいかね?」 母自身も死が近づいていることをまるで把握 していないようだった。

あれから既に十年以上の時が経つ。

夢に出てくる母は決まっていつも虚ろげで悲しそうである。 母の死の衝撃は明るく元気だった頃の母の姿を私の 記憶から消し去ってしまったのだろうか。

母は喫煙者だった。そして母の死因は肺がんである。ガンの宣告を受けたと知って、初めて振り返ってみると妙な 咳をしていたことに気がついた。元気な時は泣き言が多かった母が闘病中は一度も弱音を吐かなかった。放射線治療 で髪が抜けて、初めてカツラを被った際に至っては私たち家族がデリケートな気持ちになっていたのにも関わらず、 母はおどけて見せてゲラゲラ笑っていた。

運転中の母は決まってChaka KhanかWhitney Houstonを聞いていた。同じ曲が流れる度に妹と私からクレームが 入った。ど田舎で洋楽を聞きながら運転する母親を私は密かにカッコいいと思っていた。

2017年の始めに、その年の夏に実家が取り壊されるとの知らせを父から聞いた。 2007年の中越沖地震の影響で脆 くなっていた家を大家が取り壊すことに決めたそうだ。 母もいなくなって自分の育った家も無くなるのかと思うと 空虚感に襲われた。 翌年、実家のあった場所に向かうと更地にされた土地が目に入った。まるで最初からそこには何もなかったかのよ うに雑草が微かに風に揺れていた。 数年前、父の実家にあった古びたビスケットの缶から母の古い写真を見つけた。今までに見たことのない母の幼少 期の写真や、結婚前の母の姿が写った写真たちがランダムに詰め込まれていた。 新しい母の表情を見たような気がした。

写真家として今一番撮影したい人物は母、文子だ。しかしそれは不可能なことである。母が残してくれた記憶を 辿ってこの本を通して彼女の人物像を描くことにした。

SO MUCH LOVE, IT'S A SHAME

by Ana Vallejo

by Ana Vallejo

For the first time, I am looking at myself in silence for prolonged periods of time. Through research of neuroscientific and psychological journals, therapy, interviews, and anonymous inquiries I am exhaustively scrutinizing my fears, desires, obsessions, and defenses.

I am photographing, collecting, and recapturing traces in all the mediums that become available to me, transcribing my unprocessed and obsolete inner workings into another version of myself.

Our eyes meet and a chemical reaction takes place.

A rush of dopamine increases my focus as we simultaneously scan each other’s presence.

Unconscious attraction drives me to know this person and the experience proves to be exhilarating, an intense print of pleasure has been formed in my memory again.

Quickly, my source of gratification shifts and becomes a bit more elusive, a red flag of what is ahead.

Intermittent reinforcement is always the most irresistible and reckless, my reptilian brain is in charge from now on.

I can’t control my surroundings, and stupidly cling tightly. At every hint that the source of my energy, focus, and pleasure might vanish, I fall into despair.

In this hypervigilant state, every disturbance in my surrounding is sensed with suspicion.

My anxious nature knows this road a little too well. The thrill has been asphyxiated.

At this point he is miles away from my reach. Prolonging the situation will only lead to increasing degradation.

Then again, if I had been given any control in this process I would have most likely also fled.

I find myself in isolation fearing a void within myself. “How can you not provide yourself with your own sense of worth?” The weight of this judgement inundates all my mental spaces.

My thoughts lose continuity and the blob of fragments overwhelm me, I can only process that I am not fit for this world.

ABOUT THE PROJECT

I want to know what the experience of falling in and out of love feels like to you. Fill out this anonymous form to be a part of this project.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Ana Vallejo is a Colombian photographer who is viscerally attracted to color and emotions. She is fascinated with human perception and with how art and social bonding expand our sentience and concept of self.

Ig: @anacvallejo

anacvallejo.com

MONTAGE AND ART DIRECTION BY FOTODEMIC

KAGEROU

by Yusuke Takagi

by Yusuke Takagi

Kagerou is the heat haze on a desert lake. Invisible, pervasive decay powered by the nuclear radiation. It was 12 March 2011. The day after the Fukushima nuclear disaster, I woke up in a shrouded Tokyo. The cityscape looked blurred and twisted. Nobody else seemed to notice. For 37 million people it was business as usual. Compared to the visible devastation of the tsunami, the invisible hazard of contamination seemed to belong to another world.

The ghostly exclusion zone surrounding Fukushima Daichii nuclear plant felt more real. The danger was showing its consequences. The nature was starting to reclaim the town. It felt like walking in a floating world painting, everything was silent.

Two years later my beautiful son was born. His mother and I are still wondering what the effects of the radiation are while he was in her womb.

In the wake of Fukushima Daiichi meltdown, I face the fears of the nuclear era, pondering pregnancy and fatherhood in a transfigured Tokyo with the landscapes of the Zone and the portraits of people who decided not to leave.

Is the image of Kagerou just an illusion, or was the nuclear heat haze showing the true nature of things? Life goes on, no matter whether you are in Tokyo, Yokohama or Fukushima, we are at the mercy of politics and fate.

「陽炎」、それは砂漠の中の泉、放射性物質の崩壊熱、目に見えず、そして拡散する。福島第1原発が津波の被害を受けた翌日の20011年3月12日、静寂が支配する東京で目覚めた私は視界がぼやけ、歪んでいることに気づいた。原発から250キロ離れている東京では何事もなかったかのように日常が営まれていた。津波による目に見える被害とは異なり、目に見えない放射能汚染の危険は別世界のように感じられた。

福島第1原発を中心とした無人の避難区域の存在が、私にはよりリアリティを増して感じられた。やがて自然は再生を始め、町をも飲み込んだ。静寂が町を支配し、まるで絵の中の浮遊した世界を歩いているかのようだった。

2年後、玉のような息子が誕生した。彼がまだ母親の胎内にいた頃から、私たち夫婦は胎内被爆の影響を未だに案じていた。

この物語は、福島第一原発のメルトダウンをきっかけに放射能の恐怖に否応なく飲み込まれた私が、息子を授かって父親となり、変貌した東京の風景と同時に避難区域となった土地の風景とそこに残ることを決意した人々のポートレートを撮影した写真が織りなす物語である。

「陽炎」とは単なる幻影だったのだろうか。はたまた核分裂による熱によって物事の本質が炙り出されたのだろうか。東京であろうが福島であろうが、政治と運命に翻弄されながら、それでも我々の人生は続く。

I majored in Sociology at Meiji Gakuin University and since graduating, I’ve been a photographer based in Japan. I always try to put my conscience on neutral and see society as it is. For me, to tell a story is to understand society and myself. In addition to making my own photographs, I also use archives and other kinds of materials if it works for telling the story.

Kagerou consists of two different stories, Fukushima and Tokyo. About a month after the Fukushima disaster, I went to Minamisōma, which is about 30 km from Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant, and documented the landscape and the people who decided to stay. I visited there often. Apart from Fukushima project, I shot the landscape in Tokyo and my son, who was born two years after the disaster.

I was trying to think of how to publish the Fukushima project with multiple layers. There have been many stories published about Fukushima. I finally decided to combine the Fukushima story and the Tokyo story so that I could show Fukushima from a unique point of view - a father’s point of view. I tried to avoid the typical narrative that is often told about radiation. Instead, I used many metaphors, in hopes of drawing attention to the invisible fears and anxiety around it for the future.

Radiation and viruses are invisible, and many news stories about them, including true and fake stories, appear on TV and SNS. Because of this, fears spread dramatically like a virus and people become fearful. Poor people are always affected most by these disasters. After the Fukushima disaster, people were forced to be separated from nature, but this time people are isolated and realize how important nature is. Whatever happens, life goes on.

Human beings are fragile. We realize we are helpless in the face of nature. There seems to be no choice but to accept everything that happens and to try our best to live. It’s time to understand that we should give up the idea of destroying and conquering the virus. Instead, we should coexist with it in this pandemic situation. I believe we can adapt ourselves to our new circumstances.

www.yusuketakagi.net

Buy the book